Hi friends 👋,

Happy New Year, I hope you all enjoyed the holidays!

This week’s article takes a different tone than others. Rather than speaking to any one Web3 idea, I thought it would be interesting to dive deep into a mistake we commonly make when learning new concepts: over-simplification.

The compression of ideas can act as a useful crutch as we’re getting up to speed, but holding on to old frameworks for too long can leave us with a flatland-ish way of looking at the world. It’s really the ideas on the margins that provide us with the greatest educational leverage. The good news is that if we can stay mentally agile, by being willing to discard or update stale ideas, we can trend towards ever-greater understanding.

Let’s get to it 🚀

The Long Run of Learning

Did you know that the purpose of this newsletter is to explain the present?

That’s right, though counter-intuitive to the brand, becoming ‘Future Proof’ is all about understanding the here and now. That’s because when we explain trends that will define the future, what we are really trying to explain is some recently emerged capability, consumer behaviour, or idea that has made a new phenomenon possible.

For this reason, I’ve found that looking at some present occurrence and asking questions like “Why is this happening now?” or “How does this change what we’re capable of today?” is a pretty decent heuristic for predicting the future. As surprising as Web3 is, it would have been significantly less surprising if you read the Bitcoin whitepaper in 2008 or Ethereum’s in 2013. Ethereum’s whitepaper even directly alludes to DeFi, NFTs, and DAOs in its first paragraph!

That’s why I can confidently say that the future is here today, it’s just difficult to find and not yet obvious that it’s important. It simply takes asking a few questions to stretch our model of the world into perceiving a new suite of possible futures.

The catch here is that we must avoid the trap of approaching our inquiry from too narrow a perspective. Too often we build understanding on top of frameworks that explain a trend only from a single dimension: NFTs as digital art, tokens as digital currencies, DAOs as digital companies… Understanding things in this way is like shining a light on a mysterious object, and judging it’s appearance by the shape of its shadow. We can’t forget that shadows change depending on which angle the light comes from.

It’s reminds me of the parable in which several blind men unknowingly approach an elephant, and reach out with their hands trying to determine what the animal is:

“This beast is sharp and toothy, like a spear.”, said the man who held the elephant’s tusk.

“No, it can’t be. This animal is mighty like a tree!”, shouted the man who touched it’s legs.

“Ha! You fools have got it all wrong. This animal twists and turns like a snake!” said a man holding the elephant’s trunk.

Much like the blind men, if you’re trying to learn about the beast that is Web3, no single line of questioning can provide you with a complete understanding. In fact, we may never arrive at a true understanding - only a better and better approximation of the real trend at hand. So why then do we force a social or technology trends through the lens of a single worldview?

Concept Compression

It turns out that reducing complex ideas into more distilled concepts is a feature of the human brain, not a bug. It is an act of information compression, making ideas higher signal and easier to digest. This tactic is especially effective, given that we can often achieve most of the explanatory power with only a few frameworks or core ideas.

In other words, you can approximate a good understanding of NFTs by thinking of them as digital art or tradable in-game objects. And although DAOs aren’t exactly blockchain-native companies, understanding them as such will get you pretty far. Even these major concepts constitute a sum-of-parts, and help you better understand Web3 as a whole.

Such is the nature of learning, that we are caught between the tension of true understanding and our tendency for concept compression.

These counter-productive brain habits are known as cognitive biases - systemic errors in the way we process and collect information. All cognitive biases stem from otherwise helpful behaviour, in this case giving humans a knack for creating highly sharable and neatly packaged ideas. But the problems resulting from a cognitive bias can be less obvious, which make their occurrence widespread and rather insidious.

That’s why I want to explore the adverse effects of concept reduction, to build an awareness that can counteract this specific cognitive bias. To accomplish this, we’ll explore two fundamental problems with concept compression, and explain why we should instead strive for concept diversity.

The long tail and framework inequality

Expertise as a function of nuance

The long tail and framework inequality

When we distill a concept, we are trying to reduce the number of ideas and frameworks that contribute to our understanding. The challenge here is that not all frameworks are made equal.

Imagine you are working on a puzzle with pieces of varying sizes. That’s right, whereas all puzzles have pieces of varying shape, this particular puzzle contains pieces that might be 2, 3, or even 10 times the size of a ‘standard’ puzzle piece. In trying to complete this puzzle - with the end goal being to glimpse its final image - it makes sense to start by fitting together the largest pieces first. With this approach, if the pieces were truly uneven, you might even finish close to half the puzzle with only a few dozen pieces.

This probably wouldn’t make for a very fun puzzle, but it more or less describes how we use frameworks to stitch together an understanding of concepts. We naturally gravitate to the handful of frameworks and metaphors that expose the ‘gist’ or ‘essence’ of an idea.

Our challenge here is that this approach often encounters the problem of a long-tailed distribution. Perhaps the first dozen puzzle pieces account for 50% of the puzzle’s area (green). That would mean the rest of the puzzle’s picture is spread out over ~1000 pieces (yellow)! This phenomenon occurs in learning quite frequently.

The first few frameworks and metaphors easily get us to a rough understanding of a given concept, but closing the rest of a gap is an uphill climb requiring many weeks of effort.

Expertise as a function of nuance

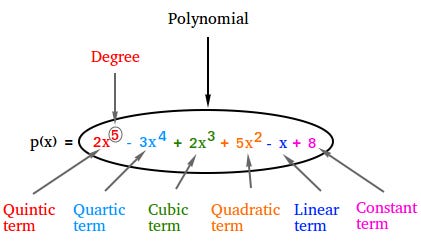

Relying on too few frameworks can cause us to miss valuable aspects of an idea or trend. Even the difference between a 90% and 95% level of understanding can be immense. We can explain this well by abstracting our puzzle to something like a polynomial math equation with different order terms (x, x^2, x^3,…).

Every piece of the puzzle is like a new term in the equation, adding it’s own nuance or detail to the image. Except, as we know, some terms are more important than others, just like how some of our puzzle pieces show more of the puzzle’s image, or how some frameworks explain more of an idea’s essence.

Now we’re going to get a bit math-y here, but I promise you’ll be able to follow along visually. Let’s say we have an equation that creates a curve like this.

The red line, our “goal” or “image”, has broad features, like it’s general upward trend. But rather sneakily, it has finer details, like the small downturn it makes after crossing x=0 right before shooting back up. If we were to approximate the red line with very few terms, we’d want to place our most important terms first:

The blue line, with only red’s highest order term, captures the essence of the upwards trend, but completely misses the nuanced downtrend in the beginning. Adding more terms here can quickly earn us a better fit:

The green line, now with two of red’s terms, has a better picture of the downtrend, but to achieve a better approximation we need even more resolution.

The reason I’ve put you through an impromptu algebra class is this:

When you are trying to understand a concept (as depicted by the red curve) the diversity of frameworks at your disposable effectively constitutes your expertise. Here we can define expertise as the closeness of our approximation graph (blue, green, and purple) to the true reality (red). And reality is full of nuance. Achieving expertise means seeking out diverse sources, even though our knowledge approximation ‘feels close’ to true understanding.

We can’t avoid that learning suffers from decreasing marginal returns; after all, we get a lot less information from our 10th article than from our first. But it's really the 10th that elevates your expertise.

To move forward in learning, we must understand that nuance is captured by the discovery of fresh new perspectives. Engaging in diverse and unique lines of questioning allows us to slowly piece together the full picture. By avoiding over-simplification and staying flexible in our mental models, we can evolve our understanding and fine-tune our image of the world.

If you enjoyed this edition of Future Proof consider subscribing for weekly content on the technology that will shape our future!

If you really enjoyed Future Proof consider sharing it with an intellectually curious friend or family member!

Let me know what you thought about this piece on Twitter.

With gratitude, ✌️

Cooper